Exploring the World’s Terrestrial Biomes A Comprehensive Guide

Introduction to Terrestrial Biomes

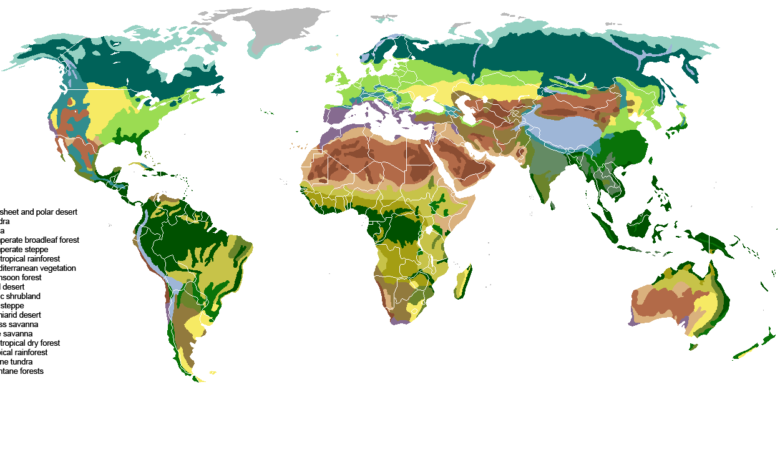

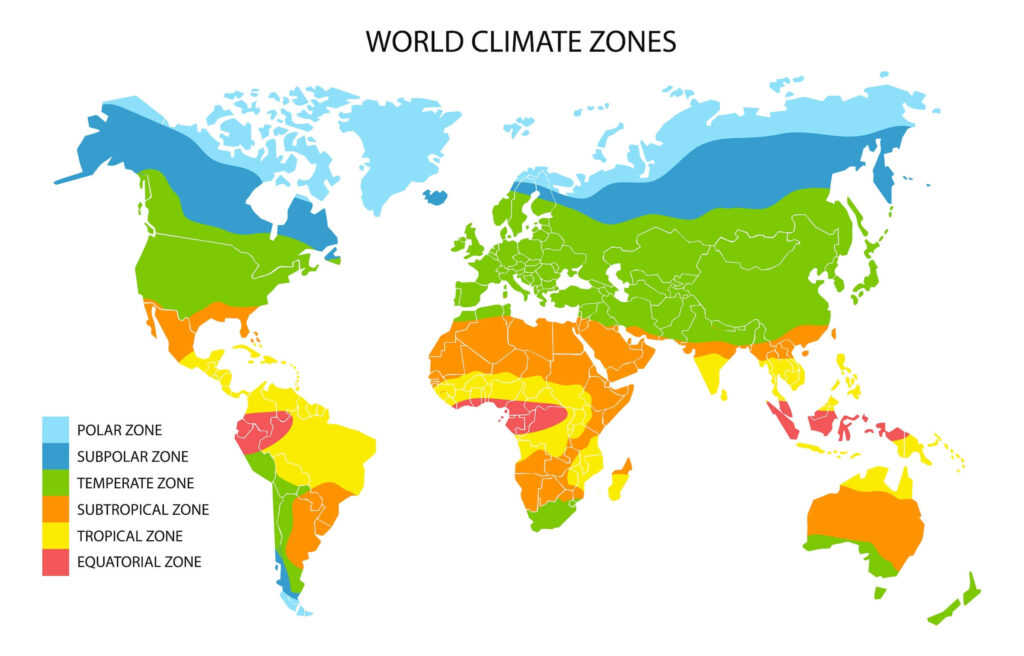

Terrestrial biomes are large-scale ecological communities shaped by climate, geography, and evolutionary processes. These regions are defined by distinct vegetation types, animal species, and environmental conditions, creating a tapestry of life across Earth’s surface. From the dense canopies of tropical rainforests to the frozen expanses of the tundra, terrestrial biomes represent the planet’s response to variations in temperature, precipitation, and altitude. Understanding these biomes is critical for grasping global biodiversity patterns, ecological interactions, and the challenges posed by human activity.

The classification of terrestrial biomes hinges on factors such as latitude, soil composition, and seasonal weather patterns. For instance, equatorial regions receive consistent sunlight and rainfall, fostering lush rainforests, while polar areas endure extreme cold, limiting biological activity. Beyond their ecological significance, terrestrial biomes provide essential resources—oxygen production, carbon sequestration, and raw materials—that sustain human societies. However, climate change, deforestation, and urbanization threaten these fragile systems, making their study and preservation more urgent than ever.

Tropical Rainforests: The Lungs of the Earth

Tropical rainforests thrive near the equator, where warm temperatures and abundant rainfall create a haven for biodiversity. Countries like Brazil, Indonesia, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo host these vibrant ecosystems, which cover just 6% of Earth’s surface but house over half of its plant and animal species. The Amazon Rainforest alone is home to 40,000 plant species and countless insects, birds, and mammals, many of which remain undiscovered. The constant humidity and warmth allow life to flourish in layered structures: emergent trees, a dense canopy, an understory of shrubs, and a forest floor rich in decomposing matter.

Despite their ecological importance, tropical rainforests face relentless threats. Logging, agriculture, and mining drive deforestation at a rate of 40 football fields per minute. This destruction not only erodes biodiversity but also disrupts global carbon cycles, as these forests absorb 20% of human-produced CO₂ annually. Conservation efforts, such as protected areas and sustainable agroforestry, aim to balance human needs with ecological preservation. Indigenous communities, who have stewarded these lands for millennia, play a pivotal role in these initiatives, offering traditional knowledge that modern science increasingly recognizes as vital.

Temperate Forests: Seasons of Change

Temperate forests, found in regions like eastern North America, Europe, and East Asia, experience four distinct seasons. These forests are dominated by deciduous trees—oak, maple, and birch—that shed leaves in autumn to conserve water during freezing winters. Spring brings a burst of wildflowers and migratory birds, while summer supports a dense canopy that shelters deer, foxes, and black bears. The cyclical nature of temperate forests fosters a dynamic ecosystem where flora and fauna adapt to shifting temperatures and light availability.

Human interaction with temperate forests has been both symbiotic and destructive. While these biomes have provided timber, medicine, and recreation for centuries, industrial logging and urban sprawl have fragmented habitats. The loss of old-growth forests, which take centuries to mature, has reduced biodiversity and soil stability. Reforestation projects and protected parks, such as the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, aim to restore balance. Additionally, climate change is altering seasonal patterns, causing mismatches in animal migrations and plant blooming times—a silent disruption with cascading effects.

Deserts: Life in the Extremes

Deserts, often perceived as barren wastelands, are ecosystems of remarkable resilience. Defined by less than 10 inches of annual rainfall, deserts like the Sahara (hot) and Gobi (cold) challenge survival with temperature extremes. Yet, life thrives here through ingenious adaptations: cacti store water in fleshy stems, camels regulate body heat, and nocturnal animals like kangaroo rats avoid daytime scorch. Even the sparse vegetation, such as creosote bushes, plays a crucial role in preventing erosion and providing microhabitats.

Human activities, however, strain these fragile environments. Overgrazing by livestock strips away native plants, while groundwater depletion for agriculture dries up oases. Tourism, though economically beneficial, often leaves trails of litter and disrupts wildlife. Conservation strategies focus on sustainable water management and educating visitors about desert fragility. Surprisingly, deserts also hold potential for renewable energy; solar farms in the Mojave Desert exemplify how harsh climates can power sustainable development.

Grasslands: The Sea of Grass

Grasslands, spanning continents as prairies, savannas, and steppes, are defined by vast open spaces dominated by grasses rather than trees. The African savanna, with its iconic acacia trees and migratory herds, contrasts with the temperate grasslands of the American Midwest, where bison once roamed. These biomes thrive in regions with moderate rainfall—enough to support grasses but insufficient for forests. Fire, both natural and human-made, plays a key role in maintaining grassland health by preventing woody plant encroachment.

Agriculture has profoundly transformed grasslands. Fertile soils make them ideal for crops like wheat and corn, leading to the conversion of 40% of global grasslands into farmland. This shift endangers native species, such as the prairie dog and cheetah, and contributes to soil degradation. Conservationists advocate for rotational grazing and the preservation of remaining tracts like the Eurasian steppe. Grasslands also act as carbon sinks, storing vast amounts of CO₂ in their root systems—a service increasingly vital in combating climate change.

Tundra: The Frozen Frontier

The tundra, Earth’s coldest biome, exists in the Arctic and atop high mountains. Permafrost—a layer of permanently frozen soil—underlies this stark landscape, where temperatures rarely exceed 50°F even in summer. Vegetation is limited to hardy mosses, lichens, and dwarf shrubs, while animals like polar bears, Arctic foxes, and migratory caribou rely on seasonal bursts of insects and plants. Despite its harshness, the tundra supports indigenous cultures that have adapted to its rhythms over thousands of years.

Climate change poses an existential threat to the tundra. Rising temperatures are thawing permafrost, releasing trapped methane—a potent greenhouse gas—and destabilizing infrastructure. The loss of ice also disrupts predator-prey dynamics; for example, shrinking sea ice hampers polar bears’ ability to hunt seals. Conservation efforts here are complex, requiring global cooperation to reduce emissions. Meanwhile, scientists study tundra ecosystems to better understand feedback loops that could accelerate planetary warming.

Taiga: The Boreal Forest

The taiga, or boreal forest, encircles the Northern Hemisphere just below the tundra. This biome endures long, frigid winters and short, mild summers, with coniferous trees like spruce, pine, and fir dominating the landscape. The taiga is the largest terrestrial biome, covering 11% of Earth’s land, and serves as a critical carbon sink, storing more carbon than tropical rainforests. Wildlife here includes moose, lynx, and migratory birds that feast on summer insect blooms.

Industrial exploitation threatens the taiga’s ecological balance. Logging for paper and timber, oil extraction, and mining fragment habitats and pollute waterways. Forest management practices, such as selective logging and wildfire prevention, aim to mitigate damage. Indigenous groups, like the Sámi of Scandinavia, advocate for sustainable land use that respects traditional reindeer herding routes. Protecting the taiga is not just a regional concern—its role in global climate regulation makes its preservation a worldwide imperative.

Chaparral: Mediterranean Magic

The chaparral biome, found in coastal regions like California and the Mediterranean Basin, features hot, dry summers and mild, wet winters. Dense shrubs like manzanita and sagebrush dominate, adapted to frequent wildfires through fire-resistant seeds and quick regrowth. This biome supports unique fauna, including coyotes, roadrunners, and specialized insects. The chaparral’s proximity to human settlements makes it a hotspot for biodiversity and conflict alike.

Urban expansion into chaparral regions increases wildfire risks, as seen in California’s devastating annual fire seasons. Climate change exacerbates drought conditions, creating tinderbox environments. Conservation strategies emphasize fire-adapted landscaping and controlled burns to reduce fuel loads. Despite challenges, the chaparral’s resilience offers lessons in coexistence—how ecosystems and human communities can adapt to recurring disturbances.

Conclusion: Protecting Our Terrestrial Biomes

Terrestrial biomes are the foundation of Earth’s biodiversity and ecological services. Each biome, from rainforests to tundras, contributes uniquely to global processes like carbon cycling and water purification. Yet, human activities—deforestation, pollution, climate change—are pushing these systems to their limits. Protecting them requires a blend of science, policy, and traditional knowledge.

Global initiatives like the Paris Agreement and IUCN-protected areas offer hope, but individual actions matter too. Supporting sustainable products, reducing carbon footprints, and advocating for conservation can collectively safeguard these biomes. As we unravel the complexities of terrestrial ecosystems, one truth emerges: their survival is inextricably linked to our own.

FAQs: Terrestrial Biomes

Q1: What defines a terrestrial biome?

A: Terrestrial biomes are large regions classified by climate, vegetation, and animal life. Factors like temperature, rainfall, and soil type determine their unique characteristics.

Q2: How many terrestrial biomes are there?

A: Scientists commonly recognize seven major biomes: tropical rainforests, temperate forests, deserts, grasslands, tundra, taiga, and chaparral.

Q3: Which terrestrial biome has the highest biodiversity?

A: Tropical rainforests boast the highest biodiversity, hosting millions of species, many still undocumented.

Q4: How does climate change affect terrestrial biomes?

A: Rising temperatures alter weather patterns, disrupt species migrations, and thaw permafrost, leading to habitat loss and ecological imbalance.

Q5: Why are grasslands important?

A: Grasslands support agriculture, store carbon in soil, and provide habitats for iconic species like bison and lions.

Q6: What is permafrost, and why is its thawing concerning?

A: Permafrost is permanently frozen soil in the tundra. Thawing releases methane, a potent greenhouse gas, accelerating global warming.

Q7: How do animals adapt to desert life?

A: Desert animals adapt through nocturnal activity, water storage (e.g., camels), and heat-resistant body structures.

Q8: What role do humans play in biome conservation?

A: Humans can reduce deforestation, support sustainable practices, and advocate for policies that protect vulnerable ecosystems.

Q9: Can damaged biomes recover?

A: Yes, with reforestation, pollution control, and wildlife reintroduction, many biomes can regenerate, though the process may take decades.

Q10: Why is the taiga considered a carbon sink?

A: The taiga’s dense coniferous forests and peatlands store vast amounts of carbon, helping mitigate climate change.